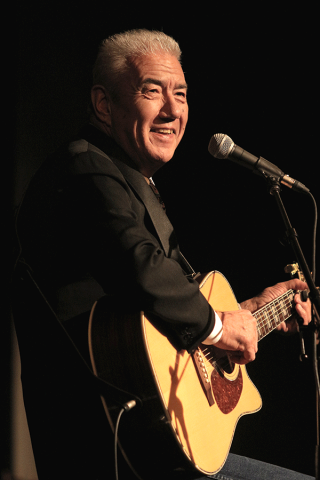

Actor, singer and philanthropist Tom Jackson, known for his roles in such popular TV fare as North Of 60, Street Legal, Star Trek: The Next Generation and Chicago Hope, was living in a crawl space, virtually homeless, as he approached the age of 40. But that soon turned around and the 68-year-old Métis, who was born on One Arrow Reserve in Saskatchewan, has since raised more than $200 million in combined cash/in-kind donations for food banks and disaster relief over the past 30 years, according to figures provided in a press release.

As the creator of Huron Carole, a Canadian touring musical production that raises donations for local foodbanks, he's helped fill millions of hungry Canadian stomachs over 22 annual concert runs since 1987 (he took a break between 2005 through 2011.)

Despite receiving accolades ranging from the Order Of Canada, the Allan Waters Humanitarian Award, the Governor General's Performing Arts Award to honourary degrees from the University of Calgary, the University of Lethbridge and Trent University, the former Trent University Chancellor continues to reveal his generous streak year-round. He's a Red Cross ambassador, and has been involved with fundraising for the Calgary Seniors Resource Society, the Distress Centre, CanLearn Society, Calgary Women's Emergency Shelter, and remains a participant in the Food Bank Canada’s Every Plate Full campaign.

His current Huron Carole tour — which includes special guests Beverley Mahood, Kristian Alexandrov and Shannon Gaye — ends Dec. 16 in Victoria, BC. He has two new apps, 364 and Pyramid of Peace, available on iTunes and Google and is filming a new TV series, APTN’s Red Earth Uncovered, as well as planning another that involves art therapy for children.

Jackson spoke with Samaritanmag about his work.

It's amazing the amount of work you do with so many charities. How do you do fit it all in?

For me, it's a labour of love. Most people set their alarm and get up with some trepidation wondering what they're going to do in that day. For me, when I wake up, my day starts with excitement because there's always something on my radar that allows me to get joy from doing what I do. It's for those who work on the frontline. I try to increase their backline so that they can do more on their frontline ‘cause I'm not always on the frontline, so they are what inspires me. I try not to think that what I do is inspirational. What I simply do is try to help and encourage organizations that continue to work on the frontline in various capacities, whether it's a woman's shelter or a recovery centre or the other myriad of charities that we support.

I see that you have raised over $200 million. What kind of difference has that made? Have people realized that you were the catalyst behind a lot of this?

There's a wide scope in the answer to that question. I think that we have [made a difference]. Because of the ongoing and consistent policy and integrity and intent of our projects, it has given us and the others the opportunity to know that they can rely upon the Huron Carole once a year that will support their organization. On the other hand, has it made a difference? I think, in a small way, we've helped to fill the gap of need. There's a large gap between the haves and the have-nots, and I'm not making a case for anything except to say that gap has always existed. Our goal has always been to narrow that gap so others can function in their capacity to create a better world.

That sounds holier than thou, but it really is the reality. If you go down the chain a little further, I have people — because we also do these awesome events on Christmas Eve, where Alison, my wife and I and others that participate on Christmas Eve, we have dinners for homeless people in various cities, and it's so awesome that I know people who have been coming to these events as beginners for two decades. When they first came to dinner, they came to eat, and now they come to serve. And they have children that help pour water for people that serve others. There's a lot of people I know that, for lack of a better description, make reservations to come to our dinner. That's the micro, but that's really on the frontline. The macro is we help others who do this all year around.

I think that the opportunity that comes but once a year. I have 11 months to prepare for what is always a magical journey for me, both for the cast — whoever that happens to be — and the participating communities, whomever they happen to be, because they're not always the same. The Christmas season only lasts for a month. Throughout that period of time, we spread the message that one should be conscious of giving, in most cases, hunger, a voice, not only between Christmas and New Year's, as a metaphor, but also New Year's and Christmas. So we look forward to being able to pass that message along and hopefully inspire others to regain what may be or reinforced with whatever they see as the Christmas spirit.

Is The Huron Carole an autobiographical story?

It is designed to be musical theatre. It's now a story about a homeless person that volunteers at a shelter. And it is the people from around that shelter who, for all intense purposes, might be musicians. There's a familiar ring to this, isn't there? The characters are caricatures, and the music is music that you're familiar with, and the story is an event that happens, which is a benefit concert gala event. The people come to support the shelter on the nights is the audience, so the audience becomes a character by virtue of the story. But the story itself is the story of this homeless person. The character that I play in the show, his name is Four Out Of Five. But he says, you can call me 4. And there's a character, her name is Bea. And a guy by the name of Will. And then there's the Christmas rappers. And it's a rap group. So all the characters in the show actually play roles. They're all musicians. So it's designed now that if Tom Jackson gets hit by a bus, the show can live. I imagine, what if Sarah Slean played the part of the homeless person? It doesn't have to be a homeless guy. So if Sarah Slean, this wonderful actress, played the part, would it fly? I asked around and people said, ‘Well, that would be interesting.’ And that's totally the right answer. What if Tom Jackson gets hit by a bus? What do you? Does it go away? No, it doesn't. Does it have a life? Yes, it does.

When you decide to help, what key component helps you make that choice?

In a lot of what I do, is, at this point, I'm a clown, and people will come and see my tomfoolery, my song, my storytelling. And it's because it's in aid of something greater than me. So I'm that clown that will perform and help those organizations do what they do, but really, I'm a one-trick pony. And if I have the time and they have the machinery that they can best use to be effective and promote an event, I'll participate in the event. I wish there was a more romantic story than that, but that part isn't interesting. What is interesting is that most of those organizations find the courage to come and find people like me, that they do that and it's our choice as to whether we want to participate or not.

Yes. All the money that comes in at the gate goes to the local charity, and we also encourage our events to be a rallying point for other sponsors to make additional contributions to the charity.

When did you first realize you were making a difference?

I've said selfishly, that helping someone else — and it's important to say this, because it's not just about those who are obviously in need — it's about me, who needs to do what I do. That sounds like a riddle, but it's not. When I figured out that my place on the planet, my time on the planet, had some value, which was simply by helping somebody who needed help, and it was that verb, that action, that made me realize that I could be worth something, that I could make a difference, and that difference would only be as significant as I was going to be in my actions. And, if one can make the claim that as an artist, others follow you, they watch you, that if you can lead people in direction by example, do good for others, help others, then it has a ripple effect and we go on blind faith that that does exist.

Was this realization part of your upbringing? I understand for a while that you were homeless and on the street.

It came from that period, which was not from my childhood. I was 38-years-old, living in a crawlspace. It was really a hole. It was under somebody's house where you couldn't stand up. And it was in that time that I came across someone who was in distress — certainly worse off than I was — and by the grace of god or the creator or whatever supreme power you believe in, it sent me an angel, in my opinion. And I didn't save that angel's life; that angel saved mine, in my opinion.

Where did this happen?

I was living in Toronto.

What was the first action you took as a result of this?

I realized I was ill-equipped to do what I ultimately wanted to do, so I went to an organization that was an emergency referral centre, and the soup kitchen — not to get soup, but to serve soup. That's what became an impetus for me — that I could actually realize helping that organization by using the little skills that I did have, which really was being a pitchy singer (laughs) and calling a couple of other friends of mine that were much more efficient at playing and singing, and saying, this organization is short of some hampers — let's see if we can raise some money so they can buy hampers or buy the food that they needed for that Christmas. That was a seed which ultimately grew into a national, televised event 10 years annually, raising millions of dollars. And as you can see from the schedule this year, we're traveling once again to 15 cities from rock-to-rock — we've gone from St. John's to Victoria. That, in itself, is a statement of those communities, to, the satellites, the people that have joined in this effort. It's a real credit to the communities that are out there. They're the mustard seed in Victoria. These are people who I've had a relationship with for a long, long time, so the other selfish part about it is that I get to see all my friends from across the country. I only see them once a year, and I can't tell you how exciting that is.

You're also an ambassador for the Canadian Red Cross. What do you do as ambassador?

In defining itself, the ambassador role, we really didn't know what that was. I say we — myself and the Red Cross — didn't know what that was exactly when we started. What it came to be was the realization that I could go into communities in stress, and connect with people who needed something that they weren't able to express for whatever reason, and would find the freedom to express that to me. Then I would go to those who are actually skilled enough to provide the help. Let me give you an example: I went into an area — there was a pod where people had been evacuated to — and I ran into a young lady who was in tears. She became real distressed and I asked her what was the matter. There was no one else in that room but me and the people who had been evacuated this pod. This girl was in tears because she needed a shoelace. But you know, when you get into a debate about something and that's not really what the debate is about? There's something else going on, you know? So it wasn't the shoelace - there was a lot more going on there. The shoelace was the lynchpin, the key to the gate. So I went back outside that facility and I said, 'Who does shoelaces here? I need somebody who does shoelaces.' And somebody put up their hand, who was in the organization, and I said, 'Okay, come with me.' I connected everybody up, and it really, clearly, for me, at that stage, defined what my role would be going down the road: it was to make myself available to go into places where people were in distress and try to help them, try to facilitate them, connecting up with people who could provide what they needed.

You’ve been to La Loche (a town where four people were killed in a shooting spree and seven others were injured in January 2016), Fond-Du-Lac (where forest fires forced evacuation) and a few other places in Saskatchewan. Seeing the devastation, how does that impact you?

It makes me smarter. It makes me realize that out of the mouths of babes comes great knowledge. Let me give you an example. I was in front of 700 students and I asked the question, “If you want to see a better world, say 'Aye.'

And if you want to see a better world, say 'Love.'” I had a room with 700 kids, and some of them were standing back against the wall. And we were there talking about community-building and anti-bullying and things of that sort. We encouraged positive reinforcement, and I asked, 'Is there anybody in this room that understands what a superhero is and what love is?' And one young man sitting on the floor in front of me put up his hand and says, 'You don't have to teach us kindness, Mr. Jackson. You only need to be kind to us.' And I said, 'Okay, what do you think a superhero of kindness is?' And a little girl sitting next to him leaned over, and whispered in his ear — and it was a loud whisper, the whole room could hear it — and she said, 'Love.' And he repeated that, and everybody in the room — those who had been standing against the room with their arms folded, and others — their arms were now down by their sides, totally relaxed. But it came out of the mouths of babes. So I get smarter every day when I'm out there meeting young people, and certainly elders, who are always smarter than me.

Do you head to these scenes during the actual tragedy?

Not within the timeframe. I'm usually there after-the-fact. For instance, I had an experience relative to the Fort McMurray event [a wildfire that began May 1, 2016, destroying approximately 2,400 homes, forcing the largest wildfire evacuation in Alberta history and spread across approximately 1,500,000 acres before it was declared under control on July 5], but I wasn't in Fort McMurray. I went to Edmonton to see if I could go into the areas where people were evacuated before any of that happened. Normally I would be in a hotel, as were many others. And I was in this elevator, and there was a young man who was getting in just as I was getting off the floor. And out of curiosity, I asked him, 'How are you doing?' He said, 'I'm good. I'm awesome.' And I asked, 'Where are you from?' 'I'm from Newfoundland.' So I said, 'What brings you here?' He said, 'Well, I'm here because yesterday I was in Fort Mac and I had a home. Today I don't have a home. Yesterday, I had a car. Today I don't have a car. And what you see on me,' — and this was just a 30-second elevator ride — 'what I'm wearing, is all I own. But you know what? I just got off the phone talking to my sister and she's safely evacuated from Fort Mac, so I'm doing crazy good.' And this is somebody who had nothing all of a sudden. It puts all that into perspective. So yeah, okay, I wasn't on the ground there, but I certainly got a sense and a feel, not only because of that incident, but the communication that I have that comes into my stream from the Red Cross.

What are your thoughts on the Dakota Pipeline protest (a protest against the underground oil pipeline project in the U.S. has been staged by local native Americans in Iowa and North and South Dakota - especially Standing Rock - expressing environmental and land ownership concerns, with demonstrators in August 2016 and some celebrities drawing attention to the issue.)

It would be remiss for me to make a comment about something I know little about. But I can say this: Because we have the right to speak, because we have the right of voice, if we don't use that voice, then what's freedom about? It doesn't matter whether you're pro or con about anything - you have the right to have a voice, and if you don't use that voice, I think you're missing the opportunity to create change. So that's what I can say about it.

Any thoughts about the Gord Downie Secret Path Fund for Truth and Reconcilation? (In 2016, Gord Downie recorded the album Secret Path, based on a 1967 Maclean's Magazine article called The Lonely Death of Charlie Wenjack that described a young native boy named Chanie who died while trying to escape the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School, a place where aboriginal culture was demeaned and their culture and language was being eradicated, part of a bigger problem and one that Downie alleges was conducted with the tacit approval of the Canadian government.)

Yeah, that's one of the things that perpetuates what I just said. Gord Downie is making a statement. And it's awesome that he's making that statement. I think it's fantastic that he's making that statement. The truth and reconciliation issue is something that everybody needs to address and accept that this is our country. This is us. And what does this say about us if we don't care about ourselves? If we continue to think of others as others, there will always be others. But if we don't think of others as "others," then they're part of our family.

You also published a book, 364 - TImeless Wisdom For Modern Times. Was that to impart knowledge to those that might be in need?

Absolutely. It's all positive reinforcement. I call it shoebox knowledge. Over the years — and more recently over the last couple or three years, I want to consider myself a writer, so I walk around with a pen and paper. You'll very seldom see me walk around without a notebook, because if I don't write things down, I don't remember them. But often people do or say things, and I go, ‘Hmmm, wasn't that an interesting thought?’ Then I'd write it down. And it may be not something that I would have said, but it caused me to think and rethink it, and paraphrase it so that it makes sense to me. And then I take that piece of paper and I throw it in a shoebox so that I know where it is.

So now I have a shoebox full of notes, and (wife) Alison said, 'You should organize that stuff,' and that's where 364 came from. So it's a book of positive reinforcement — 364 thoughts where I encourage you to go into the book, and for each thought, you write something under it, so the book provides for that. And if you do that for all of the pages in this book, on day 365 you will have written your own book of positive reinforcement. And what power would that have if only 10 people did it? Or 100 people? Or 1000. Imagine if you had 1000 books of nothing but positive reinforcement? Extrapolate that. What if I told two people? In six weeks you'd have more books than people on the planet.

Do we need charity more than ever?

I think we need to be aware more than ever, because the dynamics of the world are changing. I don't necessarily believe that we're paying enough attention but I also don't believe that there's no attention being paid. The enthusiasm, the intelligence and the minds of young people today are very similar to days gone by and I'm very fortunate to see it go by again. I'm 68, and I'm telling you that in 1965 to 1975 there was something very similar in the world going on as there is today. It was young people having a voice and people who had less, gaining more power, as they were having more access to outlets to voice their frustrations because they needed sea change. It happened in London. It happened in the U.S. It's happening in Canada. It's happening all around the globe, where people who have less are realizing that they have more than they think they have.

Air Jordan III (3) Black/Cement 2011