Dekpor is a village in southeast Ghana that is so tiny, most maps of the country don't even include it. There are no rich families. Nearly everyone, including children, tend rice and cassava crops to survive. Many cannot afford the medication to cure malaria, which costs between $5 and $20. The closest hospital is hours away and only three motorbikes are available in the village to get sick or pregnant people there. There is no running water and electricity is unavailable in most homes.

Many families there cannot send their children to school because they're unable to afford the basic supplies and uniform and if a child is needed at home for farming, education is out of the question. Those who attend Dekpor Basic School, which currently enrolls 650 students, are thrilled to be there.

The destinies of Dekpor's students are changing, due to the efforts of two Toronto-area schoolteachers, Linda Chow Kordze and Carol Sheardown, directors of the Dekpor School Development Organisation (DSDO), along with Andrew Sanderson who came onboard in 2010. The group is trying to assist Dekpor schoolchildren by improving the quality of their school, as well as their livelihood in one of the country's poorest villages.

"Linda and I are about as grassroots as you get. We're two teachers who are very determined," Sheardown told Samaritanmag in an interview in Toronto. "In two short years, we've built a library; we have renovated the junior high school rooms; we have renovated the administration building; we have fixed up the primary classrooms; we've built a water reservoir, we've got kids being sponsored; two teacher-librarians being paid for. We're getting things done."

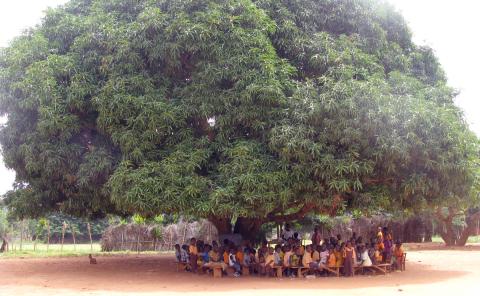

Just three years ago, Dekpor Basic School consisted of a few dilapidated buildings, but most classes were held outside in thatch-roofed structures or under trees. There was no library. To this day, students show up to class hungry, hence the need for the breakfast program. Paper is so scant - and needed for the older students - that the kindergarten kids practice the alphabet by drawing in the sand with their fingers, relays Sheerdown, who has never been to Ghana, but receives regular email updates from Kordze, who is now based there.

Kordze, explains Sheardown, first became interested in the region when she took a Ghanaian drumming course in Canada.

"She got quite into [drumming] and decided to take a trip to Ghana to find out more about it. She took a subsequent trip and visited Dekpor because she wanted to carve her own drum," Sheardown says. "Being a teacher, she took a walk to the closest school and was shocked by what she saw. She came back home and decided she needed to do something about it."

After Kordze's first summer in Dekpor, she had three big wishes, Sheardown says. "She wanted to get kids sponsored; she wanted to build a library; and she wanted to get some Canadian teachers over there to volunteer."

After returning to Toronto in late 2009, Kordze decided to sell her Toronto home and move to Dekpor permanently, so she could oversee operations in the village. Meanwhile, Sheardown joined her team and started the day-to-day groundwork in Toronto.

Among Sheardown's chief responsibilities are raising awareness at schools across Toronto's York Region, as well as marketing, correspondence, fundraising and providing content for the website.

"My approach has been through schools because that's my comfort level. I like the approach of making kids think twice," she says.

She also emphasizes that DSDO differs from larger organizations that can pay for advertising. "We don't have the overhead," Sheardown says. "We try to do everything as economically as we can. We don't want to waste any money."

The first major task completed by DSDO from donated funds was a new library for the students. Villagers from Dekpor all laboured to cut the cement blocks for the building. Meanwhile, sponsors gave enough to hire two teacher-librarians to run the library during the school year. With every trip to Ghana, more books are taken in luggage by Kordze and other travellers (such as Kordze's family and the volunteer teachers). There are thousands of books there, now she says.

"The librarians had their work cut out for them. The kids got a hold of these books and they didn't know how to open them," Sheardown says Kordze told her. "They just didn't know how to hold a book or how to turn a page."

Beyond running the library, the staff teaches adult literacy courses in the evening. Newly installed lights ensure that these classes can take place later in the evening, without interfering with the daily farming work. In these classes, the adult students learn Ewe, their native language, and those that progress the furthest begin to learn English. Around 30 adults attend these classes, which take place three nights a week.

DSDO try to fix the rooms without wasting money. When a block of three classrooms needed renovation, they were horrified when the painter wanted an exorbitant amount of money. In response, they figured out a plan to give a "hand up, not a hand out," as Sheardown puts it, and got the community involved.

"I said to Linda, 'Can you teach them how to paint?' So that's what we decided to do," Sheardown says. "All of the kids who were actually in those three classrooms [as students] sanded down the rooms. And then we hired four of our senior students to do the painting. It gave them a sense of accomplishment. Nobody in Dekpor's ever painted before."

One of DSDO's most recent accomplishments was a water reservoir, completed in May and funded entirely by Sheardown's son's grade 8 class. The Dekpor community dug in to help build the 14-foot deep reservoir, with every family bringing a representative to the dig site to help with the labour.

Although the water isn't entirely clean, it is an improvement on what students were consuming before. "Their moms will tell them to go get a drink of water from the grungy stream, and they know it makes them sick, but at least their stomach's full," Sheardown says. "Now there's going to be some good drinking water."

The two directors have organized sponsorship programs to bring new supplies to the students. The public can also donate money to fix unstable walls and holes in roofs, as well as build new classrooms.

One fund that DSDO recently started is for a breakfast program, which gives sponsored children and needy students a nutritious breakfast each morning. The students get a rotational serving of eggs and a small piece of chicken or fish, along with rice and a vegetable stew made from cassava and maize.

It currently costs $100 to feed a child breakfast each year. "We are, just as of this week, giving our sponsored children and 'breaky kids' lunches now too," Sheardown says. "But keep in mind 650 kids, and only precious few are receiving this food - the truth is they all need it."

Another sponsorship program at the school is to fund teachers, who have difficulty instructing large groups of children. It is hard to find certified teachers, Sheardown says, and many will not work or volunteer at the school because it does not pay well. It costs $1,000 to pay a teacher's wages each year.

One of the teachers at the Dekpor Basic School, ironically named Patience, volunteers to teach 150 to 170 kindergarten students. It takes her half an hour to do attendance, and then she sits under a tree with a chunk of chalkboard and begins the lesson, relays Sheardown.

One of the most exciting moments Sheardown heard about from her co-director - who keeps in touch with her via an Internet cafe three hours away - was when the Dekpor Basic School received soccer jerseys from Aurora, Ont. students.

"Linda had [the jerseys] printed with 'Dekpor Schools' on the bum of the shirt, and the kids went nuts. They ran around shrieking. They couldn't contain themselves," she says. "They ran into the village and half of the joy of the kids in those pictures is they've never had shoes on their feet."

"Philip was also one of those kids who painted [the primary block and the library] during his Easter break. He's a kid who's got guts and he's determined," Sheardown says. "Linda is very taken by him and his personality and his will to survive and his drive, his enthusiasm. I think he's going to just keep working until he is something. He's just a kid who won't stop."

People who sign up to be a child's sponsor are expected to do so on a long-term basis. In 2011, DSDO began a summer school for sponsored students. Due to the normal ratio of students per teacher, the classes were successful, Sheardown says.

Teachers can also volunteer at the school during the summer. Eight teachers from the Greater Toronto Area helped out in Dekpor in July 2010, and others are expected to volunteer this summer.

Since its inception, DSDO has raised more than $50,000 for the students and teachers. But Sheardown insists that those funds are just a sliver of what's needed.

She believes that with more fundraising, many kids at the school could get health insurance to fend off typhoid and malaria. "We'd love to see all of the kids in the school with [health insurance]," she says. "It costs five cedis [or about $8 CDN] if they're under 18 years old. Families cannot afford that."

Other needs include expanding the breakfast program and getting new materials to build new classrooms. She estimates that each classroom will cost between $20,000 and $25,000 to build, and 11 are needed to keep up with present enrollment. Four more reservoirs - at the price of $2,000 each - are also in the works.

"We can't do it all right now. We don't have the money. But look at what we've done," Sheardown says. "It's small steps at a time. We know we've got a lot of work ahead of us but we're determined. And so far with anything that we have funded... we've been very happy with the results."

newest nike shoes for girl CD0463-401 – Buy Best Price Adidas&Nike Sport Sneakers