On paper, the rescuing of orphaned children from conflict zones or regions devastated by natural disaster is exemplary, but the reality is complex, and the danger lies in failing to acknowledge those complexities under the blanket notion that adopted children are always “better off” when the contrary is not being adopted at all.

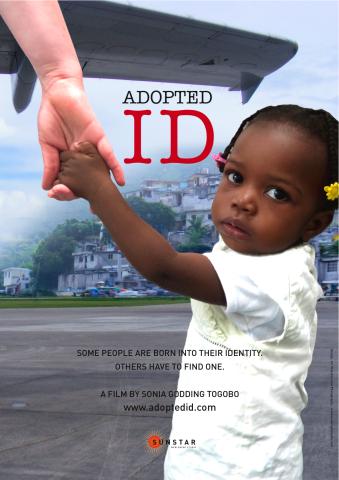

Accepting that generalization is not enough for filmmaker Sonia Godding Togobo, who examines the issues surrounding transnational and transracial adoption in her debut full-length documentary, Adopted ID.

The film chronicles the journey of Judith Craig, a young woman who returns to Haiti to search for her biological parents, a task that seems increasingly impossible as Craig arrives without any leads and only 27 days to do it.

A foundling, Craig was abandoned by the side of a road when she was only four days old. She was subsequently adopted by a Caucasian Canadian family who provided a stable home, but that stability wasn’t enough to shield her from a lifetime of internal conflict as she struggled with her racial identity. It’s that conflict that drives Craig to uncover her roots.

“I want to continue the dialogue around race because I feel like, in the so-called post-racial America that we’re headed towards, the idea of color blindness is creeping up,” Togobo tells Samaritanmag about her motivation behind examining transracial adoption. “It almost means that if you’re post-racial you’re skin colour and culture shouldn’t matter anymore. It’s still a taboo conversation, especially in Canada, and I think ideas of race have to be challenged consistently.”

Togobo’s view that skin colour and culture should matter finds powerful support in Craig’s experiences. Throughout the film, Craig and her adoptive family speak honestly about Craig’s struggle with alienation. Her mother relates a story about her own experience attempting to navigate the cultural divide: learning to comb Craig’s hair (to anyone familiar with the issue, black women’s hair is the subject of extensive debate that ties in notions of acceptance and self-esteem). And in one particularly unsettling scene, which is sure to provoke debate, Craig visits an orphanage in Haiti and is troubled at seeing the influx of Caucasian families interacting with and considering adoption of black children despite the reality that this is her own family makeup.

“It’s a challenge because the counter argument is always, ‘So it’s better for these children to be in orphanages?’ and I don’t believe that,” says Togobo. “I believe that, of course, it’s better for a child to be in a home that has love, but I feel like I have higher expectations for us in this generation. Of course, that’s the foundation, but I feel like love is not enough.

“The family is so integral to one’s identity that if a child doesn’t feel confident enough as a person, as a result of not being able to express things they’ve been feeling or not being able to have these feelings validated, there’s repercussions to that. And I think sometimes well-meaning, adoptive parents think it’s enough to have food on the table and provide a loving environment, but I think from the little experience I’ve had with transracial adoptees it’s not enough.”

Togobo isn’t alone in recognizing that support and resources are needed to educate and aid families who have engaged in or are considering transracial adoption. The filmmaker first met Craig at an event hosted by the London, UK-based Transnational and Transracial Adoption Group, which facilitates “networking and contact opportunities for adoptees whilst recognizing, respecting and valuing each individual's diverse adoption experience and the resulting lifelong impact upon them,” according to its website. In her research, Togobo also discovered summer camps aimed at transracially adoptive families.

“Part of the problem is we know there’s some kind of issue, but sometimes people don’t want to hear the truth about it, so I feel like I’m trying to bring perspective with the film in that regard,” says Togobo. “I’m hoping that Judith is a voice for transracial adoptees who are quite young. I hope in the future they can find this film and just look to someone who’s done it because guilt can sometimes hold [adoptees] back from even allowing themselves to entertain the idea of trying to find their biological family. So I hope the film can be a piece of inspiration for someone.”

Adopted ID premieres in Toronto at the Hot Docs Bloor Cinema (506 Bloor Street West) on July 19 at 6:30 p.m. Tickets can be pre-purchased for $12 at www.adoptedID.com

nike roshe split blue hero size 8 women jeans