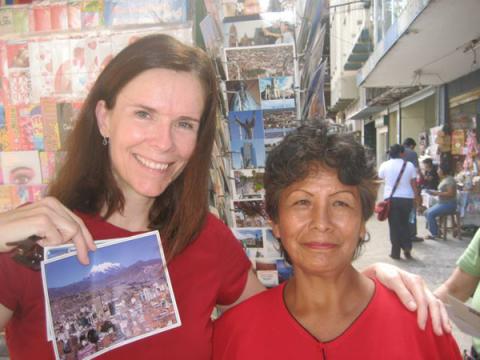

In February, Flanagan, a former nurse, travelled to Bolivia with a group of volunteers that included her sister Jean, a physician in Vernon, B.C., to provide glasses, eye surgery and optical support for the residents of Santa Cruz.

“It’s a great thing for someone who doesn’t necessarily have a medical background, because you get this wonderful hands-on experience,” she says. “You are giving people glasses, and it’s really a very intimate exchange that you have with them. In some cases, they haven’t seen clearly for many years, and when you put glasses on them suddenly they can read. It’s very moving.”

MMI was started in 2002 by Christian missionaries struck by the urgent need for health care in the poverty-stricken areas where they were working. The organization recruits doctors, nurses and administrative staff from North America to volunteer at clinics in Latin America and Africa. Just as importantly, it partners with local churches and other organizations to train local people to continue the work after the volunteers have gone home.

Flanagan got involved with MMI through her sister, who works with one of the project’s opthalmologists in Vernon. “This group has a strong Christian focus, but the religious side of it isn’t what motivates me,” she says. “My interest is more in the experience I’m having. They’re very open about that, and they say you don’t have to be Christian to do it—you just have to care genuinely about helping the poor, and that’s your reason for being there. So there are two types of people who go. I do have a religious background, but my motivation is more on a humanitarian level.”

Flanagan herself worked for two weeks fitting glasses at the clinic. When she and her fellow volunteers arrived there each morning, they would find about a thousand people waiting to be seen. “They were screened initially to see if they had problems with distance, and then they were seen by my sister or one of the other physicians to see if there were other medical issues that might explain what was going on with their eyes,” she explains. “Next, they were seen by optometrists, and eventually they made their way back to our room with their prescription, which had been entered into a computer database.

“The donated glasses had all been catalogued and cleaned and repaired and then entered into the database, so then we had to find the closest match,” she continues. “There was this whole room full of boxes of glasses; it took a massive amount of organization and it was run with military precision. I was so impressed by the organization there. I mean, you rarely get that kind of organization in First World countries, never mind the Third World. So they retrieved the glasses and I’d put them on the patients and adjust them, working with opticians who were training me on the fly on how to fit glasses.”

Flanagan also worked to find reading glasses for people who had had eye surgery and had come to have their eyepatches removed. “Those were really the Hollywood moments,” Flanagan says. “These were people who’d literally not seen for decades, in some cases. They were often older, and they might have had a granddaughter with them who was kind of their seeing-eye person. And this little girl had been denied a bit of her childhood, always having to show Grandma around, so she was freed up suddenly to have her life, and Grandma was freed up to be able to be independent again, and the feeling is incredible when you take that patch off. Some of them are just stunned; you can tell that they’re having to process the fact that they can see.”

Flanagan was particularly touched by the reaction of one older man to his new vision. “Their families always stand behind them very respectfully, hands on their shoulder, and when the bandage came off, I was talking to him and joking with him a bit, practising my terrible Spanish, and then I thought, ‘Oh my God, he hasn’t even looked at his family yet!’ So I said, ‘You don’t want to be laughing with me; you want to see your beautiful daughter!’ And without skipping a beat, he said, ‘Well, a father doesn’t have to have eyes to know that his daughter is beautiful.’ And then, of course, I burst into tears, and the daughter burst into tears. I’ll never forget that moment.”

One man in his 60s who came to the clinic looking for glasses had a prescription of -16, which means he was nearly blind. “We looked and looked for a pair of glasses that would help him, and we were able to find some really old ladies’ glasses and we put them on him,” Flanagan says. “And he grabbed one of my hands and said, ‘You have saved me from depression.’ For the past year, he hadn’t been able to work because his job had involved writing numbers of machine parts on paper, and he wasn’t able to do it so he’d been unemployed for a year. And now he had these huge old-lady glasses and he was just beside himself; he was so thrilled. Glasses like that would have cost thousands of dollars because the prescription is so specialized.

“It moved me when I looked at the glasses because they had probably belonged to someone’s grandmother who had passed away, and I thought about what pleasure she would take to know that someone had taken the time to donate those glasses and ship them off, because it changed not only his life but his whole family’s life. It’s incredible, really.”

Of course, sometimes the donated glasses turn out to be expensive designer brands, which Flanagan enjoys immensely. “I find it hugely amusing when I pull out Giorgio Armani or Alain Mikli lenses,” she says. “It just goes to show you—it’s just about whether you can see, not whether it’s a drugstore or a designer lens. I had one lady who got these Alain Mikli glasses. I remembered that particular series because I’d actually interviewed him about them, and here I was seeing them in this setting. I tried to explain to her that I had actually met the designer of these glasses, and she looked at me like I was from another planet. I told her, ‘You scored!’ But when you tell them what the cost of these glasses would be, they just can’t believe it.

“Given what I do here at ELLE and the kind of world we operate in, it’s a very wonderful counterpoint to all of that, and it keeps all kinds of things in perspective.”

Air Jordan 1