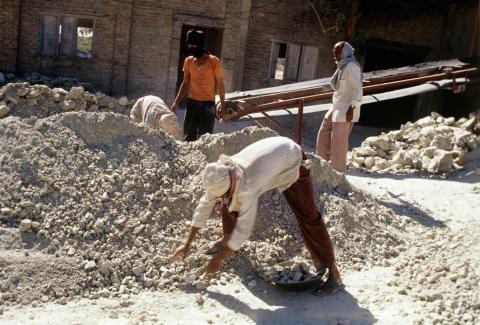

Her latest film, the gripping documentary Breathtaking, investigates the Canadian asbestos industry. Valued since pre-history and commercially mined since the Industrial Revolution, asbestos was nicknamed the “magic mineral” for its fabric-like properties and its capacity to protect against fire, and was used in everything from home insulation to oven mitts.

Just one problem: asbestos is a proven carcinogen that has been banned by more than 40 countries, including every member nation of the European Union, as early as 1992 in Italy and 1997 in France. Yet, it continues to be legally mined here, primarily in Quebec and almost exclusively for export to Third World nations with less stringent legislation against toxic substances.

Canadian asbestos is not just mined; it’s essentially subsidized: each year, the feds and the Quebec provincial government give $500,000 to the Chrysotile Institute, a registered asbestos lobby group.

Breathtaking tracks asbestos from current-day mines in Thetford, Quebec to India and beyond, highlighting the work of anti-asbestos activists determined to ban the stuff universally. But Mullen’s role as witness and whistle-blower came about for a most unfortunate reason: in 2003, her father, Richard, succumbed to asbestos-related cancer, mesothelioma.

As the film points out, asbestos has a remarkably long latency period, so those suffering its affects today were likely exposed decades ago. Richard Mullen traced his exposure to a job site in Aruba in the 1950s where he worked as an inspection engineer.

It’s cold comfort, but Richard Mullen’s fate was hardly unique. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labour Organization put the current annual death toll from asbestos-related cancers at 90,000. Of the asbestos mined in Canada, fully 98 percent is exported for use elsewhere, primarily Asia and India. The remaining two percent is mostly used in brake pads.

Mullen — who also serves as director of programming for Planet in Focus, Canada’s leading environmental media arts organization — spoke with Samaritanmag on the cusp of her film’s Toronto premiere February 24, 7 p.m., at the Royal Ontario Museum, where she will lead a panel discussion following the film.

“No not really. I mean, I suppose I was a feminist and a believer in human rights and social justice, but I was not an activist. I certainly didn’t think of myself in that way. But I have been galvanized by making this film. I am socially conscious and community-minded about issues that affect people’s health.”

What adjectives would you use to describe your father?

“Generous, good-natured, traditional. And I think he would have been very proud of my film. My mother is very proud and she is actually attending the Toronto screening with my sister.”

Making the film, were you surprised there hasn’t been more outrage directed against the asbestos industry and that the global community of activists and media hasn’t been more outspoken in condemning Canada’s continued involvement in the mining of asbestos?

“Yes. There have been campaigns staged, letters written, people speaking out about it, newspaper articles and TV, but it doesn’t really seem to be having the effect people are hoping for, which is that the asbestos industry is closed down in Canada. I feel like the issue is in the public consciousness, but the industry is still not being stopped.”

So where is the bright light on the horizon with this issue?

“I don’t know. But it is a dying industry — so many countries have banned the mining and use of asbestos, including the EU, so I think Canada and the U.S. will eventually have to follow, but it does seem to be taking longer than I think it should. As the film shows, in Quebec there is a long, complicated history between the government and the asbestos industry. It’s obviously a key component of the asbestos story in Canada. I mean, why is Quebec still mining asbestos? It’s a complicated question.”

“I tried to get government officials in Quebec on camera, but every time an interview was scheduled they kept cancelling. I think that happened, like, five times. In the end I said, ‘OK I’m just going to make this from my perspective.’ The sense I got from the officials was that I was just going to give asbestos a bad name. I think they have a party line and they didn’t want me to interview them because they felt I was going to slam them. I know what they say about why asbestos is mined but, in the end, I remain unconvinced. I think you can easily poke holes in their argument.”

What about the unions such as the United Steel Workers? What has been their role or position on the mining of asbestos?

“To be honest I really don’t know about that. I think unions now are fighting for their workers, but historically, I am not sure I can speak to that.”

I suspect a key challenge in making this film was finding that middle ground between creating a kind of valentine for your dad while exposing the menace of this industry?

“Yes, that’s absolutely the case. It was a kind of valentine to my dad as a worker, that he was exposed to this through his work. We have this idea that we go to work and we’ll be safe and we can trust our employers. Maybe that’s a naïve notion, but most of us do trust that we are not going to be harmed by our work. And it was really important to me to tell that story. Even though my dad lived a good and long life (he died at age 80), he still did die of this disease. So that was crucial. But at the same time, it was important to me to look globally: it was not only my dad who got sick. It’s hundreds of thousands of people. Every time I would tell someone about this film, someone would say, ’Oh yeah, my dad or my grandfather or whoever also had that.’ It was astounding.”

“Well, I am a filmmaker so I also wanted to present this from an artistic place. That’s why I use a lot of [family] photographs and Super-8 film. Films are made for many different reasons and while I hope activists will see it, I hope they’re not the only ones who see it. If I can do screenings across the country and it gets people talking and if I can get a TV broadcast and get the word out, that’s the ideal. Maybe we can shame Canada into changing, but as a filmmaker it’s also a project I am proud of. This presents a family’s perspective on the asbestos issue. To that end, there have been some victims groups that have contacted me to see the film because our story is like their story.”

What’s next after the screening in Toronto?

“We head to Ottawa, then to Sarnia, Hamilton, definitely Vancouver and Victoria and eventually the U.S. Dates are pending, but we are in the planning process. I have been working with the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization in the U.S. and they plan an annual conference, which I attend in the film in Detroit, so they hopefully will organize a webcast for sometime this fall.”

30 Winter Outfit Ideas to Kill It in 2020 - Fashion Inspiration and Discovery